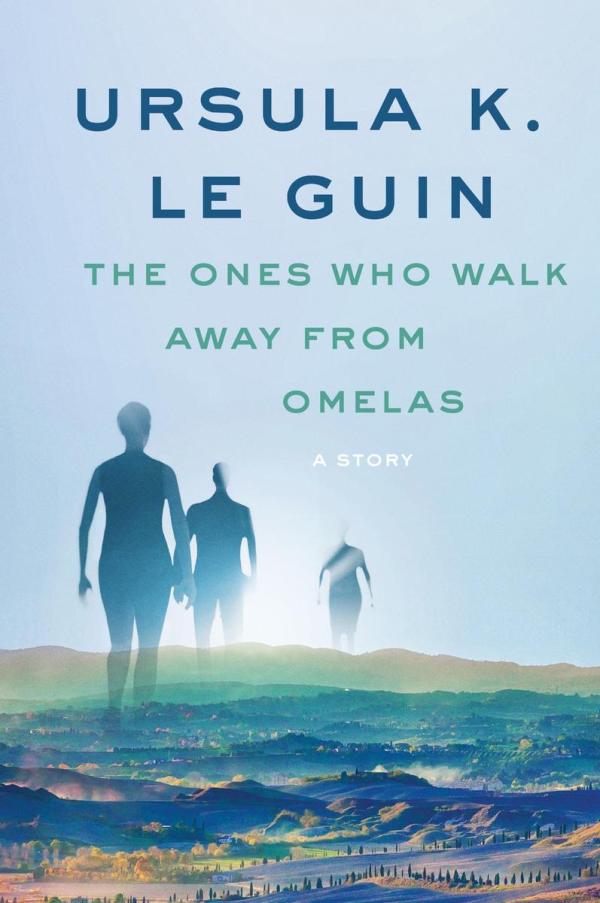

The Ones Who Walk Away From Omelas By Ursula K. LeGuin

Well, then. I forgot I have to be literally anywhere else.

With a clamor of bells that set the swallows soaring, the Festival of Summer came to the city

Omelas, bright-towered by the sea. The rigging of the boats in harbor sparkled with flags. In the

streets between houses with red roofs and painted walls, between old moss-grown gardens and

under avenues of trees, past great parks and public buildings, processions moved. Some were

decorous: old people in long stiff robes of mauve and grey, grave master workmen, quiet, merry

women carrying their babies and chatting as they walked. In other streets the music beat faster,

a shimmering of gong and tambourine, and the people went dancing, the procession was a dance.

Le Guin, Ursula. The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas. 1973.

Why we loved it

No surprise—we loved this story. Ursula K. Le Guin crafts a deceptively simple utopia, a glittering city of joy where every happiness depends on one horrific condition: the endless suffering of a single child. In just a few pages, this razor-sharp tale forces us to confront uncomfortable questions about morality, complicity, and the cost of “perfect” societies.

After reading N.K. Jemisin’s brilliant rebuttal (“The Ones Who Stay and Fight”), we had to revisit Le Guin’s original—and it absolutely holds up. There’s a reason this 1973 story remains a cornerstone of speculative fiction. Its power lies in what it doesn’t say: Le Guin never judges those who choose to stay in Omelas, nor those who walk away. She simply shows us the bargain and asks: What would you do?

The Unanswerable Dilemma

Could you knowingly accept paradise if it required a child’s torment? Would you have the courage to walk into the unknown, even if it meant collapsing the system? Or—more disturbingly—would you rationalize staying? Le Guin’s genius is making readers sit with that friction. There’s no heroic third option, no revolution brewing. Just the quiet, devastating choice between two impossible paths.

A Legacy of Discomfort

Decades later, Omelas still mirrors our world’s own moral bargains: the exploited workers behind our gadgets, the marginalized communities bearing society’s hidden costs. That’s why this story sticks—it’s not about a fictional city, but about us.

So we ask you: Walk away, or tear it all down? Drop your thoughts below.

Leave a Reply